Alright, I’ll admit it: I have a complicated relationship with Catherine of Siena.

Yes, I refer to the fourteenth century nun and mystic. Arguably Europe’s most famous female writer and sainted Christian of the late medieval period, she has long drawn my attention for her impressive achievements. She had an outsize influence on charitable and devotional life in Italy (and thus the rest of Christendom) and very nearly brought the Avignon Papacy to an early end through her impassioned pleas. In an age when few women held significant political power or enjoyed a wide readership, Catherine of Siena stands out as a shining star in the vast expanse of medieval Europe.

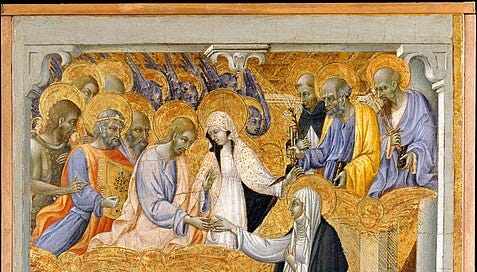

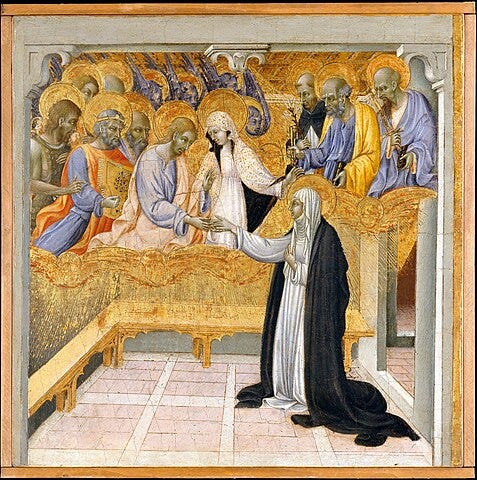

Nevertheless, certain aspects of St. Catherine’s story have always struck me as odd. The aesthetic extremes to which she pushed herself in pursuit of holiness offend my Protestant sensibilities. The tale of how she sucked pus out of a woman’s wound to grow in sisterly love for her seems more grotesque than anything. Ditto for her vision of her mystical marriage to Christ, in which she was outfitted with a ring made of the Savior’s foreskin. They feel like the kind of things you would say to slander a person as insane rather than hallmarks of Christian devotion.

But surely, I am too skeptical. For St. Catherine, these were not mere physical acts, but moments of great spiritual significance. If I can believe the stories in the Bible, some of which go beyond the grotesque into the positively macabre, I should be willing to give Catherine a hearing. I may never understand what possessed someone to cut off this poor woman’s head after her death and put it on permanent display, declaring it incorruptible despite the obvious lack of soft tissues. But I can certainly understand why people find her life inspiring.

I wish to keep an open mind about St. Catherine. I may not believe God has called me to venerate her relics, but I see how she was used to bring light to many who lived in darkness, and that is worthy of honor. Yet, even as I applaud her as a Doctor of the Church, I simply must say it: the woman was weird, full stop.

She is hardly the only one. The more I learn about the thousands of saints who have filled the two millennia of Church history, the more I see that this weirdness is a feature and not a bug. Saints spend their time doing things that most of us would never do. In fact, if we were to do them now, people would deem us mad, bad, or both.

Allow me to draw a comparison. Among the many colorful anecdotes about St. Catherine is how she finally convinced her family to allow her to pursue a life of consecrated virginity. They had wished her to marry and have children as the daughters of wealthy Sienese families were wont to do. But at an age when most girls would be chiefly concerned with their social lives, Catherine wanted nothing more than to pursue Christ through cloistered contemplation and the mortification of her flesh.

Naturally, Catherine’s parents thought she was out her mind, and were this story taking place today, none of us would blame them. Teenagers as a group are not known for their exceptionally good sense. Indeed, they are prone to flights of fancy and reckless behavior. So, her parents refused her permission to enter the cloister, and Catherine responded by cutting off all her hair. In this way, she sent a message to her parents that she was forsaking the life they envisioned for her — that she did not value what they valued and would not draw her identity from their familial life together.

This incident reminds me of a (then) young lady with whom I was friends during my college days. She came from a relatively traditional Christian family who had sent her to a Christian school as the start of what they no doubt hoped would be a particular life trajectory. But when I witnessed her talking to them on the phone or mentioning them in conversation, I could tell that she chafed under their supervision. She did not share their values. She did not wish to identify with them.

Then one day after a school break, this friend arrived on campus having cut off all her hair. As with St. Catherine, this was not a mere fashion decision. My friend declared she was no longer a Christian. Not only that, but she was a lesbian. As soon as she finished up at that Christian college, she moved to an obliging East Coast metropolis where she began to live a life which seemed as far from the context in which she was raised as possible.

Both these women took the same action to signal that they were rejecting familial and societal expectations. They would not take the standard path laid out for them. They were stepping outside the bounds: transgressing the limits of typical righteousness.

The outward actions of these two women were similar, but their internal motivations were absolutely opposed. My college friend was consciously rejecting Christ, whereas St. Catherine was consciously pursuing him. That may be the only difference between “sinners” and “saints,” for both are known to reject the situation in which they were raised, the expectations placed upon them, and the easy path upon which most tread. Both offend those who know them and earn the titles “weird” and “strange.” But one does so for love of Christ, and the other for love of self.

Most of us are familiar with the Parable of the Prodigal Son. It was the late Tim Keller who first drew my attention to the fact that the father and son are both prodigal. (No, he didn’t tell me this personally. I read it in The Prodigal God.) It was one of those observations that makes you ask, “How on earth did I not notice this before? I’m an idiot.” At least, that was how it struck me.

The word prodigal means 1) wastefully or recklessly extravagant, 2) giving or yielding profusely, or 3) lavishly abundant.1 From those definitions, one can see how the term could be used either positively or negatively.

In the parable, a son demands that his father grant him his entire portion of the inheritance immediately. This is highly unusual for a two reasons. First, a person is typically dead before anyone can inherit property from them. Second, in the culture of that time, land was usually inherited rather than liquid funds due to biblical imperatives about keeping property in the family. The father would have had to sell part of the family estate to make the asset liquid, i.e. turn it into currency. So, by this act, the son is declaring he wishes his father was dead and doesn’t care a whit about the family estate or reputation.

The son then takes the money and goes wandering in a far country, giving it away lavishly in exchange for all sorts of luxuries. He ends up destitute and must return home in disgrace to beg forgiveness.

It is easy to see how the son is prodigal given these circumstances. But the father also turns out to be prodigal in his own manner, for he lavishes love upon the son, accepting him back without hesitation and heaping gifts upon him. He even slaughters the family’s prized cow (no small asset) to have a celebratory feast. The father is therefore as prodigal in his love—heedless of what anyone will think or what is customary—as the son is in his lack of love.

This parable is often framed with two villains: the younger, prodigal son and the older, judgmental son. But there is another way to view the story, with the elder son as the middle of the road, typical human being and the younger son and father as two radical extremes. The younger son despises laws and the elder son lives by them—so I often hear in explanations of the passage. But truthfully, the father also despises the law: a law that he as much as anyone put in place. For the elder son appeals to a standard that is seemingly one of long standing. I imagine him thinking, This is not the way this family runs. We don’t do things like this. And that could refer both to the prodigality of the younger brother and that of the father.

Extreme saints and extreme sinners are both prodigals. When Catherine of Siena entered the consecrated life, she kept nothing for herself: not wealth, not clothes, not hours of sleep, and not even basic sustenance. She lived as simply as she possibly could and gave everything to the poor materially, emotionally, and spiritually.

I would argue that this is irrational behavior, and I use the term advisedly. We can rationally conclude that if every person on earth followed Christ’s command to the rich young ruler to sell all he had and give it to the poor, we would end up in a circular situation where the final person in the chain would have to throw all the world’s resources into the ocean or some such insanity. If everyone gives everything away, then no one has anything left to give. This is the difficulty in taking many of Christ’s dictates in the Sermon on the Mount to their logical end.

But while God is the source of true logic and reason, he reserves the right to violate both as necessary. He set the laws of nature in place but acts supernaturally all the time. He can be the prodigal father, transgressing the bounds for the sake of humanity. He can be the ever giving one because he is the eternal one. He is perfect, unending benevolence.

We, on the other hand, are creatures of limitations. If everyone had pursued the same celibate life of St. Catherine, humanity would have died out. If everyone had gone into the desert and lived a hermitic life like St. Anthony, the Scriptures never would have been copied and they would have been lost. The Church has long realized this, and thus in medieval times there was a two-tier approach to Christianity: a group of super saints in monastic orders who lived such perfect lives that they had merit to spare, and the average people who had to harvest the crops, make the babies, and build the structures. The first estate—those who prayed—could be prodigal on behalf of those who fought (second estate) and those who worked (third estate), saying Masses for their souls.

You will not be shocked to hear that I do not believe this is the ideal model for Christianity. (I am still Protestant, after all.) Rather, I believe every Christian is called at times to show love that goes beyond the bounds and will strike many as prodigal. We are not called to make sacrificial financial gifts to every charity that exists, but we will be called to make such sacrificial gifts on occasion as the Spirit moves us. Some of us will show extreme love in a life of celibate service, while others will show extreme love in raising several children.

The strange things we do on behalf of God will be different and suited to our individual vocations, but the motivation will be the same: love of God and neighbor. If no one does everything but everyone does something, we can create a world that looks a bit more like the Sermon on the Mount.

So, while in one sense my life is nothing like Catherine of Siena’s, there is an important way in which we are similar. We are both pursuing Christ, holiness, and growth in love. What God asks me to do will be different, but the motivation will be the same. I need not be scared or shamed by St. Catherine’s story, but realize that we both serve the same Lord through whom we have all our righteousness.

Which means, I think, that my relationship with Catherine of Siena isn’t that complicated after all.

I wrote a book! You can purchase Broken Bonds: A Novel of the Reformation here.

At least, this is what Dictionary.com claims. https://www.dictionary.com/browse/prodigal

Each saved soul had its place in the body of Christ. Like pieces in a puzzle, we each have unique shapes and colors and fit precisely in a place which God created for us. I will not judge someone else who is sincerely following Christ just because their path is different than mine. Thanks for a very interesting article.

This is the kind of recovery of "the great cloud of witnesses" that makes learning about the saints fun! As a C. S. Lewis-style Anglican, I'm thrilled to see you doing this work and sharing your discoveries Amy!