A Broken King

An Advent meditation upon oppression and kingship

If you have been reading my articles for a while, you probably know I have a special affection for T.S. Eliot’s poem “Little Gidding,” the last of his Four Quartets. (See for example this article and this one.) I am hardly unique in this regard, but the fact this poem remains so beloved is surely no mark against it. It is a rare jewel.

This Advent season, a particular phrase from this poem has echoed in my mind: one that hits hard in the year 2025. In the opening portion of “Little Gidding,” Eliot describes the small chapel that gives the poem its name. It is dedicated to Saint John the Evangelist and located in rural Cambridgeshire,1 not especially close to any major city. At this remote location in the middle of the 17th century, an Englishman named Nicholas Ferrar established a religious community consisting of his own family members. Although they were laypeople and not clerics (Ferrar alone was ordained as a deacon.), they pursued personal piety in Christian community, studying Scripture, praying, and serving their neighbors.2

This communal experiment did not survive Ferrar, and while the chapel continued to stand, it was largely forgotten by the English people. That is, until T.S. Eliot discovered it in the 20th century and wrote a poem about it. In “Little Gidding,” Eliot describes a hypothetical visit to this sacred site.

“If you came this way,

Taking the route you would be likely to take

From the place you would be likely to come from,

If you came this way in may time, you would find the hedges

White again, in May, with voluptuary sweetness.

It would be the same at the end of the journey,

If you came at night like a broken king,

If you came by day not knowing what you came for,

It would be the same, when you leave the rough road

And turn behind the pig-sty to the dull facade

And the tombstone.”

The phrase “like a broken king” always grabs my attention as I read this poem, and it has captured my imagination again this holiday season.

I admit, my feelings toward kings are at an all-time low. Here I refer not to individuals who bear the formal title, such as the constitutional monarchs of Europe whose roles are largely ceremonial. I am thinking of those who are kings (or queens) without the title: the people on earth with the greatest degree of power over the lives and destinies of others. The rich, the powerful, the famous—these are the true kings of our day, and among them are the greatest oppressors.

The language of oppression is highly controversial, so let me be clear: when I speak of oppression, I mean it in the sense of the Old Testament prophets. An oppressor is someone who enriches themselves at the expense of the vulnerable, imposes injustice on society, spews lies and degradation, and opposes the will of God. Yes, when I speak of oppression, I mean it in the sense of the Book of Ecclesiastes.

“Then I looked again at all the acts of oppression which were being done under the sun. And behold I saw the tears of the oppressed and that they had no one to comfort them; and on the side of their oppressors was power, but they had no one to comfort them.” (Ecclesiastes 4:1-2)3

I appreciate that the Bible fully acknowledges the evils done on this planet. Our hearts are revealed in those pages. We are not fundamentally good people who will do the right thing unless circumstances happen to drive us into error. Rather, we receive good things and destroy them. We hoard the riches of creation for ourselves. We use power not to serve others, but to make others serve us.

I am not suggesting we are all oppressors of the worst order. Some of us commit far more evils than others. But within us all is that selfish, prideful tendency to hoard, control, and oppress in ways great and small. Because kings have more power than the rest of us, they can impose their will in ways the rest of us never could. That is why they become the chief oppressors of the people.

If I say “oppressor,” who immediately pops into your mind? Probably a politician or business tycoon. Those are the true power brokers in our world: the ones who command the law and the money. Not all politicians are oppressors, nor are all business tycoons. Some do an admirable job stewarding the resources they have been given for the good of others. But you can surely think of a few egomaniacs who merit the title oppressor: people who increase the misery of those more vulnerable than themselves while expressing disdain toward those same people. These are kings, and oppressive ones at that.

Although these types have always existed, I have been unusually aware of them this year. Every time I scan social media or read the news, the oppressive nature of many of our kings is on full display. Not once do they admit their errors. Not once do they behave with grace. I often find myself wishing God would break them: that he would miraculously enable their overthrow, acting to defend his people. In my flesh, I even want oppressors to suffer as they have caused so many others to suffer.

Yet, the fear of God leads me to pause and remember that seeking the good of my enemies means desiring their redemption. The kind of breaking that is most glorious is not the mere crushing of oppressors, but the miracle of repentance produced by God himself. Although the evils of kings are often more public and cause greater damage, they are rooted in the same sinful nature that bedevils all who live under that ancient curse, including me. It is not only the poor who require salvation, but also the rich. It is not only the weak who need a Savior, but also the strong. For none of us are truly rich or strong.

The Scriptures tell us repentance is the way of salvation, and it can only be produced by the work of the Holy Spirit, who grants life to those dead in sin. The truth can only be denied for so long. Evil cannot remain hidden forever. Sooner or later, whether in this life or the next, each of us will be confronted with the knowledge of what we have done and our deep need for mercy.

This is what breaks kings: the exposure of their deeds and a true reckoning of their oppression. Every king is eventually broken. The question is, will they admit it? Only when they acknowledge their brokenness can they hope to be healed. Their oppression finds its end in their repentance.

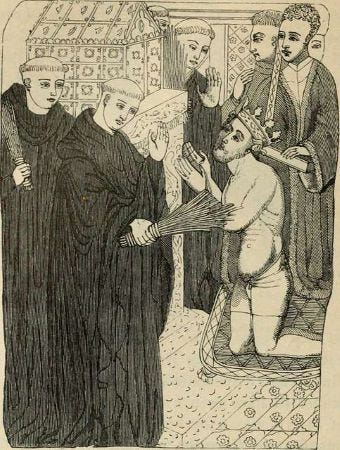

Henry II of England was perhaps the greatest king in the long history of that nation, but he too was broken, and by a saint no less. The archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, opposed Henry II’s attempts to enforce his will on the English church. The feud went on for years until Becket was lying in a pool of blood in his own church, slain by knights who supported the king. Becket was immediately deemed a martyr for the Christian faith, and Henry II was forced to walk barefoot into Canterbury Cathedral wearing nothing but a sackcloth, receive a beating from the monks, and do penance throughout the night before the tomb of his hated rival.

Henry II was a broken king, but I do not believe he truly realized how broken he was. Yes, he made a show of repentance, but the key words there are “made a show.” Although he put off his kingly garb, he was still the center of attention, performing on one of the grandest stages his kingdom had to offer. The rest of his reign told the tale: the same character flaws remained on full display. Repentance implies a turnaround, a conversion, a renewal of the spirit—and not because you have worked yourself into it, but because God has genuinely worked it in you.

Little Gidding is a small chapel in the middle of nowhere. Yes, not only is it in the middle of nowhere now, but it has always been in the middle of nowhere. There is no glorious shrine within those walls, no room for a crowd, no chance to make a show. Eliot tells us the broken king comes at night when no one can see him. His humiliation does not come through public scorn but anonymity. The broken king has not come to beg mercy from humanity. He has come to fall on his knees before his maker.

“If you came this way,

Taking any route, starting from anywhere,

At any time or at any season,

It would always be the same: you would have to put off

Sense and notion. You are not here to verify,

Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity

Or carry report. You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid.”

While Eliot’s words hold meaning for us all, he was surely thinking of one particular broken king when he wrote this poem: King Charles I of England (and Scotland), who visited Little Gidding while on the run following his defeat at the Battle of Naseby.4 Years of conflict between the king and parliament had led to open warfare, and at Naseby, Charles’s cause was dealt such a decisive blow that his ultimate defeat was inevitable, though he remained at liberty for the moment.

What did Charles pray for that night at Little Gidding? He seems to have increasingly viewed himself as a martyr in the cause of good religion. Did he humble himself before God in that quietness and seclusion? Did he recognize in his change of fortune the possible judgment of the Almighty?

His behavior over the next few years suggests he likely did not interpret events that way. While Charles gets high marks for nobility and fortitude right up to the moment he was executed, he was also a proud man who did not often admit an error. Like so many kings before him and so many who came after, he would suffer a collision between the unstoppable force of his pride and the immovable object of the law, whether human or divine.

Even so, all of us reach a point where we must acknowledge the error of our ways. We must journey not to the glories of a cathedral but the anonymity of a country chapel. We must put off sense and notion, to borrow Eliot’s words. We must come not to verify, instruct ourselves, inform our curiosity, or carry some report, but simply to kneel where prayer has been valid and cry out, “Mercy, mercy, mercy! Lord, have mercy on me, a sinner!”

In his wonderful poem “I Came at Night a Broken King,” Daniel Bishop imagines himself as the man in Eliot’s poem, visiting the chapel after dark, seeking something that cannot be found on earth.

“I came at night a broken king, with naught

But pale white petals to crown this silver hedge.

The brambles, plucked quite earnestly, then taught

My fingers, prick by prick, the fallen wretch

I had become. Lest you forget, no man

Can hint at wisdom more than God has lent,

Can sow the seeds of death yet live, nor can

Retrieve the hours—not one—that he has spent.”

This is a truth we must universally acknowledge: we have no power in ourselves. The good we have is a gift. The evil is our own doing. We are not as strong, righteous, or magnificent as we imagine. In fact, we are beggars with empty hands and stomachs, longing for the bread of heaven and the living water that satisfies. One way or another, we will be broken, and not merely by our fellow humans or the difficulties of life. We will be broken by the one who made us.

As King David wrote after he was defeated in battle, “O God, You have rejected us. / You have broken us; / You have been angry; / O, restore us.” (Psalm 60:1) As he begged following his rape of Bathsheba and murder of Uriah, “Make me to hear joy and gladness, / Let the bones which You have broken rejoice.” (Psalm 51:8) And again he prayed, “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; / A broken and a contrite heart, O God, You will not despise.” (Psalm 51:17) He had known the breaking of divine judgment. He needed the breaking of repentance.

As Christ prophesied about himself, “Everyone who falls on that stone will be broken to pieces; but on whomever it falls, it will scatter him like dust.” (Luke 20:18) And as King David so boldly declared, “You shall break them with a rod of iron, / You shall shatter them like earthenware.” (Psalm 2:9)

Make no mistake: every king will either lay his crown at the feet of the Lamb who was slain or have it broken by the Lion of Judah. Our God is a fire that both consumes and enlivens. The choice for kings and for us all is either to endure the purgation of this present time, or to suffer those flames that burn eternally. As Eliot wrote in “Little Gidding” with reference to the Holy Spirit,

“The dove descending breaks the air

With flame of incandescent terror

Of which the tongues declare

The one discharge from sin and error.

The only hope, or else despair

Lies in the choice of pyre or pyre—

To be redeemed from fire by fire.”

Bishop grasps this meaning in Eliot’s poem, concluding his own meditation with a hopeful reflection.

“I came this way upon a path all walk

And found, as Eliot said, the same as all.

My treasured notions were consumed by moth

And rust. Soon worms on pale white petals gnaw.

And yet the sky, with ashen grapefruit glow,

Gives testimony that the winter ends

With coals upon which holy breath does blow.

The same flame that devours also mends.”

How can this be? What kindles that holy fire in us and sends the winter to flight? None other than that which we celebrate in the depths of winter: the coming of the Son of God.

The baby born in Bethlehem was not only King of the Jews. He was the eternal King of Kings and Lord of Lords. A broken king, Herod, attempted to break that holy child, but the time had not yet come. Another group of kings, Magi from the East, bowed before the child, acknowledging his right to rule. They would not have done so if they had not first seen the light, and they would not have seen the light if God had not caused it to shine.

That baby would become a man who would announce the coming of the Kingdom of Heaven, a direct competitor to the kingdoms of this world. From that moment, every earthly king would have to choose to acknowledge the ultimate lordship of Christ or deny it, to break in repentance or be broken upon the chief cornerstone.

The supreme irony of history is that the only perfect king was broken on behalf of the rest of us. The King of Kings became a servant for our sake. It is the nature of broken kings to take from those they rule: never to give. But it was precisely in his breaking that the perfect king gave all of himself to us. He was pierced for our transgressions and crushed for our iniquities. As he hung in torment, he begged for mercy not for himself, but his torturers. Even now, he pleads for us. Oh, that we would come and kneel before him and receive healing from his hands!

This month, Handel’s Messiah will be performed in hundreds of locations around the world, if not thousands. The most famous portion is likely the Hallelujah Chorus. How often do we think carefully about the lyrics? And how often do we listen to what comes directly before it? Here is that section of the libretto.

43. Air

Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron; thou shalt dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel.

44. Chorus

Hallelujah: for the Lord God Omnipotent reigneth.

The kingdom of this world is become the kingdom of our Lord,

and of His Christ; and He shall reign for ever and ever.King of Kings, and Lord of Lords.

Hallelujah!

This is the good news of Christ’s kingdom, which is already and not yet. This is the good news of Christmas that Mary proclaimed.

“He has brought down rulers from their thrones,

And has exalted those who were humble.

He has filled the hungry with good things;

And sent away the rich empty-handed.” (Luke 1:52-53)

Come, thou long-expected Jesus, and inaugurate your eternal rule. For in the breaking and remaking, you have built a Church for yourself, a people called by your name. You will defend them against all oppression. You will redeem all we have broken. You will even bring oppressors to repentance, for that is the business you are in, transforming us into the image of Christ.

Merry Christmas!

Historically, it was within the county of Huntingdonshire. Boundaries and names have changed over time.

https://www.rct.uk/collection/stories/the-little-gidding-concordance/the-community-at-little-gidding

All Scripture references are taken from The New American Standard Bible (1995 edition), copyright The Lockman Foundation.

https://littlegidding.org.uk/church/windows/charles-i/

This is excellent Amy. Thanks so much.

This maybe of interest: a handful of us have regularly gone on retreat there

https://www.markmeynell.net/2020/03/11/precious-moments-in-little-gidding/

This is a really wonderful reflection, Amy! Thank you.