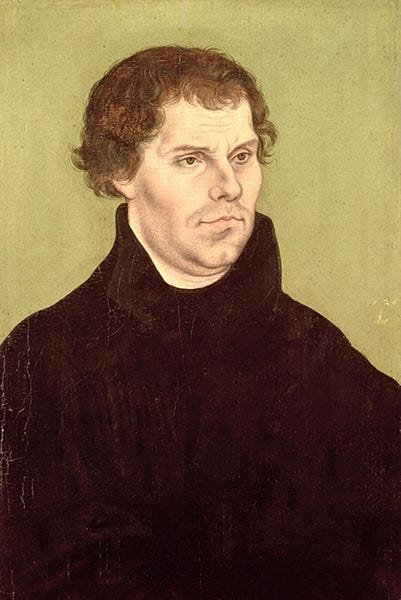

An Analysis of The Rest is History's Episodes on Martin Luther - Part Two

In which I discuss episodes four and five

Welcome back, friends! Last week, I analyzed the first three episodes of The Rest is History’s series on Martin Luther. (If you have not read that article yet, I encourage you to do so, as it provides some background information on my connection to the podcast.) Today, I will be tackling the fourth and fifth episodes. Rather than furthering adieu any further, let’s dive right in!

LISTEN TO THE EPISODES ON SPOTIFY OR APPLE.

Episode Four

This episode focuses on the events surrounding Luther’s appearance before Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at the 1521 Diet of Worms. Early on, Tom and Dom referenced their previous episodes on Hernán Cortés and the Aztecs. This was a great way to set the Diet of Worms in its proper context. Although he was a young man in 1521, Charles V was exceedingly powerful. The Spanish missions in the New World, such as that of Cortés, were bringing Charles great wealth. He ought to have been in a strong position to conquer what he took to be a rising heresy.

But he was not, due to another factor our illustrious hosts mentioned: the threat that central Europe would be invaded by the Ottoman Turks. This created a related problem. As Charles V did not have a large standing army, he relied on the nobles of his realm to help keep the peace. This meant that Luther’s ruler, Elector Frederick the Wise, absolutely had to be kept on side. From a material standpoint, this would be the chief reason that Lutheranism could gain a foothold in Germany. Tom did a good job focusing on these geopolitical factors.

The latter portion of the episode focused on Luther’s conflict with Andreas Karlstadt. Fundamentally, Luther always wants a Reformation that breaks less from tradition. He does learn some things from the Karlstadt debacle of 1521-2, realizing that the Reformation will be a long haul and differing scriptural interpretations are inevitable. Luther also respects the governing authorities and opposes iconoclasm, while Karlstadt will be far more revolutionary.

Tom was spot on when he stated that Luther would, for the rest of his life, generally take the more conservative path. It was the issue of justification that was of chief importance to Luther, followed closely by that of the sufficiency of God’s Word. Other Reformers would focus more on transforming society through moral improvement and restoring church worship to its pristine apostolic form. Although Luther seems to us a very progressive figure, his instincts were actually quite conservative. He only favored those changes that were necessary for the salvation of souls.

Finally, on the dog thrown out the window: This story is based on a comment recorded in Luther’s Tabletalk. The way he describes the event makes it seem as if he did not throw a real dog out the window but was having some kind of dream or hallucination. Luther did not think the “dog” was a dog, but an evil spirit. So, I understand why Tom and Dom continue to joke about Luther being a dog murderer, but I do not want listeners to get the wrong impression. Criticize Luther for the antisemitism, not the dog murdering.

Now, I will make some more specific comments with time stamps for reference. (Remember that the times will likely not align if you are watching the episodes on YouTube.)

18 minutes:

Tom: (On Luther’s interrogation before the emperor) “The whole thing has been structured to ensure that he can’t start freewheeling. And I think he’s very upset by this and intimidated, so he adopts a delaying strategy. He’s asked, ‘Will you recant and revoke your books?’ And he says to this, ‘I don’t know. I want to have time to think about it.’”

I disagree with Tom’s interpretation of the situation, but in fairness, many scholars agree with him that Luther was using a delaying tactic, possibly even one suggested by Elector Frederick.

I personally do not favor the “delay tactic” explanation, as I am not sure what Luther could have reasonably hoped to gain through delay. When he came back the next day, the same questions were put to him. What did he gain legally by waiting a day? Did he hope the emperor might change his mind? That would have been highly unlikely given everything that had already occurred to get Luther to that point. The emperor clearly meant business. A 24-hour respite was unlikely to change anyone’s mind.

So why did Luther ask for another day to think? Was he reconsidering his theological views? This seems more plausible, but Luther had already been given more than three years to reconsider. He had not changed his mind when interrogated by Cardinal Cajetan or when he was threatened with excommunication. It is possible that as the likelihood of death grew closer, Luther lost his nerve. There are some things that cannot really be known until they are felt.

However, I think there is another possible explanation. Luther may have simply had a panic attack, by which I mean not just that he was afraid of death, but that he had a real bodily reaction that prevented him from speaking with the kind of strength he would have preferred. There is evidence that Luther had panic attacks at other times: many of the episodes he describes of striving with the devil could be interpreted in this manner. It is also said that Luther often spoke softly at the trial, such that those in the room strained to hear him.

As someone who has experienced panic attacks myself, I have always thought the story of Luther’s appearance at Worms seemed rather familiar. Maybe that is a case of personal bias affecting interpretation, but it seems likely to me that he was unable to speak boldly as he had hoped, so he stalled for time.

I may be wrong with my panic attack thesis, but the delaying tactic thesis seems to me the weakest.

24 minutes:

Dom: “Tom, that moment, by the way, that phrase – ‘Here I stand, I can do no other,’ or however you translate it – Diarmid McCulloch in his book on the Reformation says that’s the motto not just of the Reformation, but of all modern Western civilization.”

Tom: “Yeah. Living my truth.”

Dom: “Yeah. That’s what it is, right?”

Tom: “Exactly. Yeah, and that’s why it reverberates. That’s why it has the influence it does.”

When Luther spoke those famous words, which he seems to have uttered in German so that only part of the crowd understood, he was saying something rather different than modern people tend to assume. Here is a more extended quotation:

“Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and I will not retract anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. I cannot do otherwise, here I stand, may God help me. Amen.”[1]

Please consider Luther’s words carefully. He does not take ‘conscience’ to mean that little voice in a person’s head or that feeling in their gut that makes them believe something is right or wrong. He is talking about that moral and intellectual capacity of human beings which is held in sway by external influence. In this case, the thing which holds sway over Martin Luther’s conscience is the Word of God—the Christian Scriptures.

Luther describes this in the clearest terms: his conscience has been taken captive. He has not formed himself into a moral person by making correct decisions. Rather, the revelation of God has compelled him. The very Word of God controls him. He is not breaking away from established authority but acknowledging the highest authority of all. He believes the words of the Church must be judged against the Word of God. So, he might have his mind changed by “the testimony of the Scriptures” or by “clear reason” that explains the Scriptures, but nothing else can sway him.

We tend to interpret Luther’s words “Here I Stand” as a declaration of individual moral agency and ultimate personal autonomy. But in truth, it is not a statement of ability, but inability. Luther is crediting God with allowing him to stand. He “cannot do otherwise” because God controls him, and that is why he immediately adds, “God help me.”

Luther would go on to write The Bondage of the Will, one of the most important historic defenses of divine sovereignty within Christianity. He would oppose Erasmus’ argument that human beings can accomplish good deeds by their free will. This notion of being seized by God from the outside and made captive to his Word is absolutely key for understanding Luther’s theology.

28 minutes:

Here Tom mentions Johann Cochlaeus’ account of a private meeting with Luther at Worms. It’s worth asking if Cochlaeus’ account is entirely accurate. He became one of Luther’s most vicious opponents, as Tom notes. Even if Cochlaeus would not stoop so low as to lie, he may have interpreted events in a biased manner. This was exceedingly common in the vicious pamphlet wars of the Reformation. Luther himself often mischaracterized opponents, making their views out to be worse than was the case. Again, I do not believe Luther was simply making things up, but he was reading the worst motivations into his opponents’ words and actions. I suspect Cochlaeus was doing the same thing.

28 minutes:

Tom: “Luther’s answer is that the meaning of God’s Word is plain. If the Spirit illumines you, then you will know. You’ll get it right.”

Dom: “Tom, I’m sorry. This is such obvious tosh!”

We know Dominic has strong opinions on all things tosh, particularly of the woke variety!

The view Luther is (allegedly) espousing in this case is known as scriptural perspicuity. It is another doctrine he deals with at length in his 1525 work, The Bondage of the Will. If something is perspicuous, it is clearly comprehensible to the average person. Luther did believe in scriptural perspicuity, but with some important caveats.

First, Luther believed that the Holy Spirit illumines the believer’s mind to understand the truths of Scripture. Dominic may deem this tosh, but Christians who believe in the indwelling of the Holy Spirit confess that the Spirit aids them in this way. Christ said, “But when He, the Spirit of truth, comes, He will guide you into all the truth…” (John 16:13) So, there is something to be said for this from a scriptural standpoint.

Second, Luther assumed that the individual reading their Bible would have a certain level of competence. They would be sufficiently literate and familiar with the traditional teachings of the Church. They would use the work of past generations to guide their own interpretation, and they would seek the assistance of a pastor or other spiritual authority if they had questions.

Third, the confessions of faith that would eventually be written by the Protestant Reformers make clear that scripture is perspicuous in key matters of faith related to salvation, but not necessarily on every subject. So, the average person can read their Bible and understand the basic message of the gospel, but they may not understand every theological intricacy.

In the years following the Diet of Worms, Luther tempered his views on scriptural perspicuity a bit and emphasized the need for theological education. He had thought he was standing at a unique moment in time when the Spirit of God was performing a new and strange work that would likely be followed in short order by the return of Christ. He thought God was bringing about true knowledge in the end times, but it turned out the Reformation would be a long haul with very divergent opinions. By the mid-1520s, he realized this.

Watching his own congregants struggle to understand Scripture and his theological compatriots veering off in different doctrinal directions helped to change Luther’s views on this matter, but he also came to recognize that the Reformation was going to have a different character than he first supposed and would require a longer work of scriptural study.

51 minutes:

Tom: “He [Frederick] basically says to Luther, ‘I think this is going too far. You should come out and sort this out.’”

Frederick the Wise’s territory was being threatened with an imperial visitation. This was a primary reason that Frederick pulled his support for Andreas Karlstadt. An imperial visitation meant that the emperor’s officials would come in and examine what the churches in Frederick’s territory were teaching and doing. If anything proved to be heretical, disciplinary action could be taken and the emperor would interfere more in Frederick’s affairs. The work of reform would be brought to an end. More than wanting to preserve the emerging doctrines of the Reformation, Frederick was probably most offended by the idea of an imperial power play in his territory.

Frederick clearly wanted to end Karlstadt’s more radical experiment in Wittenberg, but it seems that Luther returned without Frederick’s blessing. On January 17, 1522, Luther wrote to the Elector’s secretary George Spalatin to say he would soon be leaving the Wartburg Castle. In late February or early March, Luther wrote again to inform Elector Frederick he was on his way back to Wittenberg. Frederick wrote a letter attempting to dissuade Luther from this path, but Luther replied on March 5,

“I write all this to let your Grace see that I come to Wittenberg under higher protection than that of the Elector, and I have not the slightest intention of asking your Electoral Highness’s help. For I consider I am more able to protect your Grace than you are to protect me; and, what is more, if I knew that your gracious Highness could and would protect me I would not come.”[2]

Granted, Frederick did not forcibly prevent Luther from returning to Wittenberg, but he does not seem to have ordered it either.

51 minutes:

Tom: “On the 6th of March, he reappears in Wittenberg. He’s bearded. He’s still dressed as a knight. It’s clear that the old monkish Luther has gone for good.”

Actually, Luther was given a new habit upon his return, which he would wear until the autumn of 1524. How long he may have kept the beard, we don’t know. Luther kept up the outward show of being a friar because it was felt it would lessen peoples’ alarm at all the changes. However, he would never adopt a tonsure, engage in asceticism, or conduct many of the usual duties of his order again. The vicar general of the Augustinians in Germany, Johann von Staupitz, had released Luther from his vows in 1518, so none of this was illegal.

53 minutes:

Dom: “Tom, is that Luther swinging, or is he being consistent? In other words, is he swinging because he’s lost control of the revolution, and also his political patron is in danger of deserting him? Or is he consistent? Am I being unfair and too cynical?”

Tom: “I think he is swinging back. I think he’s very, very anxious not to lose Frederick’s patronage, not just for selfish reasons that Frederick is protecting him, but also because he feels that Frederick has been appointed by God as the guardian of the Reformation, and that its future would be threatened were Frederick to turn on it. But I think there’s also a strong element of peak…Luther is resentful that Karlstadt, who is always seen as his number two—his deputy—has taken the lead. So, I think that’s absolutely a part of it.”

Luther is “swinging” a little, but not much. He had never accepted and would never accept some of the views pushed by Karlstadt: the complete opposition to images and vestments, the questioning of the Real Presence in the Eucharist, et cetera. Karlstadt had by winter 1521-2 begun to teach things that Luther absolutely opposed. Thus, he felt Karlstadt was leading the people and the whole Reformation into error.

The particular thing that seems to have bothered Luther most about Karlstadt, apart from the aberrant theological views, is that Karlstadt took over preaching at the Stadkirche, which Luther saw as his congregation. Karlstadt had been assigned to the congregation at the Schlosskirche, which was the Elector Frederick’s own personal chapel, though it continued to hold Mass for the public when the elector wasn’t around.

The decision for Karlstadt to start preaching at the Stadtkirche seems to have been made without Luther’s input. In fact, Luther had wanted Philip Melanchthon to take up the preaching office there. That Karlstadt stepped outside his assigned role may also have particularly annoyed the elector.

Was Luther jealous of Karlstadt taking over a leadership role? One cannot rule out such common human emotions, but the disagreement between the two men was definitely one of substance, not mere style. Luther really believed Karlstadt was hurting the congregation and poisoning the Reformation with erroneous theology. On top of which, Luther was not considered superior to Karlstadt in the university context. Karlstadt had given Luther his doctorate and was the senior colleague. Luther’s fame may have been greater, but his official standing never was.

To gain more insight into Luther’s thought process at this time regarding Karlstadt, I encourage you to read Luther’s Invocavit Sermons that he preached upon returning to Wittenberg, his book Against the Heavenly Prophets that was written in opposition to Karlstadt in late 1524, and the record of a conversation he had with Karlstadt in Jena in 1524. The latter two sources are provided in a helpful translation by Ronald J. Sider, though it should be noted that Sider is more sympathetic to Karlstadt.

Episode Five

This episode focuses on the Peasants’ Revolt (also called the Peasants’ War) of 1524-5, the largest popular uprising in Europe prior to the French Revolution. Perhaps as many as 100,000 people were killed in the conflagration which began with the targeted murder of nobles and ended with the slaughter of serfs. Tom did well to point out the general apocalyptic mood that existed at this time. I have read through both Luther and Erasmus’ letters from this period The two men who were ideologically opposed, but both were horrified by the peasant uprising and saw it as a bad omen, perhaps even presaging the end of the world.

It is difficult for a modern person to understand the dynamics of the situation. We naturally side with the downtrodden peasants who want their freedom. In the beginning, that truly was all they wanted, but soon more radical forces grabbed control of the movement. Aristocrats and their families were slaughtered. A typical example occurred in the town of Weinsberg on Easter 1525. Rebels seized the castle and forced the count and his entourage to run the gauntlet while their horrified loved ones watched. The rebels then slaughtered many of the townspeople who were in no way involved.

Stories like this were the source of Luther’s fear and anger. He viewed the peasants much as we might view the protesters who stormed the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021: violent insurrectionists destroying property and threatening the governing structure. Luther believed the government was under threat of collapse and that law and order was breaking down. He took a stand not against better treatment of serfs, but anarchy.

Throughout this episode, Tom describes Andreas Karlstadt as having tremendous influence over the trajectory of the course of the Reformation. This is perhaps giving Karlstadt too much credit, for one could argue that the Swiss Reformation’s trajectory was determined more by Huldrych Zwingli, who came to his own evangelical breakthrough somewhat separate from Luther. It is difficult at times to know whether Zwingli was influencing Karlstadt or the other way around, or indeed if they were both being influenced by a third individual such as Johannes Oecolampadius. But having just finished a biography of Zwingli by Stephen Brett Eccher, I am reasonably convinced that his influence over the development of Reformed theology was far greater than Karlstadt’s.

Overall, I thought Tom provided a good summation of Luther’s response to the Peasant’s Revolt, and in the final portion of the episode, he was absolutely right to highlight and condemn Luther’s antisemitism. What I would encourage the reader to note is that a lot of time passed between the Peasants’ Revolt and Luther’s antisemitic tracts. The early Luther shows no signs of the violent antisemitism that characterized his last two or three years. The reason for this change is much debated, but one helpful analysis is provided in the article “Luther’s Last Battles” by Mark U. Edwards.

2 minutes:

Tom: “Like Luther, Müntzer thinks that a true Christian must be born again….Like Luther, he believes in a division between those who have been born again—a kind of elect—and those Christians who you brilliantly called “Chinos”: Christians in Name Only.”

Luther really never emphasized being “born again,” nor did he dismiss most Christians as “Christians in name only.” As I mentioned in the previous article, Luther’s emphasis on baptismal regeneration (a new birth in water and the Word) set him apart from many other Protestant reformers, for whom one’s profession of faith and even a conversion experience would be more crucial. Luther also never attempted to create a “regenerate church” as Müntzer and other Anabaptists would do.

Luther’s view of election was mostly influenced by his beliefs about God’s sovereignty and the nature of grace rather than any effort to separate true Christians from fake Christians. For Luther, being “born again” would always mean baptism, and those who were baptized should be regarded as Christians unless they were actively rejecting essential doctrines of the faith.

3 minutes:

Dom: “What is it with Germans in the sixteenth century and their bowels?”

Dominic will be pleased to know that scatological language was common in the German speaking lands of this period and for some time afterward. Mozart was a particularly famous practitioner. Even modern Germans are fond of scatological humor and references, though perhaps not to the extreme degree of Luther or Müntzer.

7 minutes:

Tom: “What is more, his insistence on sola scriptura—the idea that nothing is necessary unless it is specifically mentioned in Scripture—provides them with all kinds of sanctions for rebelling, say, against serfdom, which is not mentioned in the Bible.”

Sola scriptura does not mean nothing is necessary unless mentioned in Scripture, but that Scripture is the norming norm containing all that is necessary for salvation. The magisterial Reformation accepted the importance of historic theology in crafting church practice, while radical reformers like Müntzer did not.

This is an important point that our illustrious hosts did not seem to grasp throughout these episodes. Sola scriptura means no other revelation is equal to that of Scripture. Ultimate authority rests in the inspired Word of God: the Christian Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments. However, they do not contain all the information a human being might ever need. There are some topics they never address. Furthermore, a person will need the help of other Christians in interpreting them, particularly the great theologians of past eras.

The idea that “nothing is necessary unless it is specifically mentioned in Scripture” sounds closer to the way Reformed Christians would structure their congregational worship rather than anything Luther taught.

12 minutes:

Dom: (On Karlstadt’s familial situation) “And he’d married a four-year-old or something?”

Tom: “No, not quite. He’s married a nun.”

Karlstadt’s young bride, Anna von Machau, was not a nun but the daughter of a noble family. It was a status solidifying marriage for Karlstadt. She was, however, very young for marriage, even according to the norms of that time: about fourteen years old at the wedding.

13 minutes:

Tom: (On the disagreements between Luther and Karlstadt) “And inevitably, also there are big theological arguments, and the biggest one is around transubstantiation. Luther argues that Christ is literally in the bread and wine given at the Eucharist, and Karlstadt argues that it isn’t.”

Luther did not hold to transubstantiation—a metaphysical understanding of the Lord’s Supper based on Aristotelian categories—but endorsed the Real Presence view now common to Lutherans. They accept that Christ is truly present in the elements but do not attempt to metaphysically define that presence. Terminology is very important when it comes to the Eucharist. The Reformation split over this issue, so we must be careful with our choice of language. ‘Physical,’ ‘literal,’ and ‘real’ mean different things, and none of them imply transubstantiation.

Lutherans eventually arrived at the formula that Christ is present “in, with, and under” the elements of bread and wine. They believe that congregants really eat the body and blood of Christ, even if they are consuming unworthily. But again, this does not imply transubstantiation.

16 minutes:

The discussion of Karlstadt does not mention how much he had annoyed Elector Frederick even before 1517, as highlighted by Lyndal Roper in her Luther biography. When Karlstadt was granted the chance to travel to Italy, he stayed longer than permitted and made lavish purchases. Other controversies with the elector took a similar form.

To be fair, Karlstadt may have truly changed as a person by 1522 such that he no longer cared for luxuries, but the elector’s opinion was likely set. Karlstadt’s actions in the period 1517-1525 were not as pure and humble as he himself insisted, and both he and Luther interpreted each other’s actions in the worst possible way. So, it is important for us to maintain a sense of balance when we analyze the dispute. Neither party was blameless, and not all charges were accurate.

19 minutes:

Tom: “And so he [Karlstadt] ends up amazingly taking refuge with Luther.”

Dom: “Oh my word.”

Tom: “And Luther takes him in, but predictably does not squander the opportunity to completely humiliate him. So, he makes Karlstadt write a full recantation of his views on the Eucharist.”

Dom: “In exchange for his dinner or something?”

Tom: “Exactly. Yeah, well, for shelter. You know, to keep him safe.”

The demand for Karlstadt to recant his views on the Lord’s Supper was a condition for him to remain in electoral Saxony, not to remain in Luther’s house. It occurred near the end of Karlstadt’s stay. The exact details are certainly up for debate, but it seems the Karlstadt family (for it was the whole family) were well cared for by the Luthers despite Karlstadt having accused Luther of abandoning the gospel. True, Karlstadt was no cartoon villain. Luther did not treat him as well as he deserved, but none of the parties behaved perfectly, and the high tension at that time likely helped to blow things out of proportion.

25 minutes:

One thing that gets a bit lost in this description of Luther’s approach to rulers and theological opponents is the centrality of the gospel for him. You obey rulers except when you must stand up for the gospel. You tolerate differences except when they compromise the gospel. Luther believed Karlstadt, Müntzer, the Pope, and the Jews had all compromised the gospel, which was the only hope for eternal life. That is why he opposed them. He often resorted to crude insults and slanders when doing so, but there was a reason he was so angry. He truly believed they were endangering peoples’ souls.

29 minutes:

Words cannot describe how excited I am that Argula von Grumbach has been mentioned! I did not have Dominic Sandbrook reading her works on my 2024 bingo card, but praise be, it has happened! Best moment of the episode.

36 minutes:

Tom: “The Saxon princes expel Müntzer from his holding. Müntzer blames Luther for this, and this is why he is writing the abusive pamphlet in November, in which he calls Luther ‘soft living flesh,’ because by this point, Luther has really become quite fat.”

Luther had not become especially fat by this time if portraits are any indication. That began to occur a few years later as his health deteriorated and his food supply became more plentiful.

36 minutes:

Tom: (On Luther getting fat) “But also, it’s an expression of his theology. If we’re all damned…”

Dom: “Yeah. Let’s crack on. No point dieting.”

Tom: “Crack on. You know, ‘I’m elect. I can eat what I like.’”

Luther’s view was not that we should enjoy God’s blessings because we are all damned or nothing matters, but rather that we should enjoy them because asceticism is not a path to righteousness. We are made righteous by Christ alone through imputation; we cannot beat the sin out of ourselves. We should therefore enjoy sex, food, and drink in appropriate situations and amounts. He did not condone gluttony.

38 minutes:

Excellent to point out Charles V’s distractions, such as the war with France. Very key.

47 minutes:

Tom: “And I think that all of this is kind of an expression of what we were talking about before. How because Luther sees all humans as irredeemably steeped in sin—well, irredeemably unless God, of course, does choose to redeem them, to allow them to be born again—in a sense, it doesn’t really matter. You’re not going to get closer to heaven by being—”

Dom: “Killjoy.”

Tom: “—celibate all your life.”

A better explanation of Luther’s view on enjoying God’s blessings.

54 minutes:

Dom: “He thinks Protestants are elect, and that the Jews are the opposite.”

Tom: “But that’s really important. He’s not condemning the Jews as a race. So, that’s what the Nazis are doing.”

Dom: “Ok.”

Tom: “He’s condemning them as pretenders to the title that belong to, as he sees it, God’s elect, which is people like him.”

Again, Luther doesn’t think Protestants alone are God’s elect, or that all who claim the name Protestant are necessarily elect. He also did not believe that those in communion with Rome were necessarily damned. Rather, Luther looked at what these groups were teaching. If it was in line with the gospel truth revealed in Scripture, it would lead people to salvation. If it denied the gospel, it was endangering souls.

54 minutes:

Tom: “He’s not a saint. But then against that, I suppose, theologically speaking, Luther never claimed to be a saint. I mean, his whole point is that humanity is fallen, so inevitably he’s a sinner.”

Dom: “Yeah.”

Tom: “That’s the whole point of it. So, that’s why I think it’s possible to admire Luther’s courage, his insights, while the fact that he wrote what he wrote about the peasants and wrote what he wrote about the Jews doesn’t disqualify the quality of his insights, because from Luther’s point of view, he’s fallen. He’s part of humanity. All of humanity is fallen.”

Very good to point out that Luther always acknowledged being a sinner. However, also good to say this does not excuse his comments about the Jews. In the end, I can forgive Luther his failings because of what he taught about grace. No one who truly believes what Luther taught about grace ought to be prideful. But like us all, Luther was a person of contradictions and hypocrisies.

59 minutes:

Dom: “So, by the time he dies in 1546, Protestantism has now become entrenched in large parts of Germany, it has spread to the Baltic, it’s spread to Scandinavia. It’s obvious that the ideas have spread to England through Anne Boleyn and through all these sort of people importing books and things.”

Tom: “Yeah.”

Dom: “And is that effectively what’s happened? Is Luther happy with that? Does he think, ‘Great. Brilliant. This is what I wanted,’ or does he think, ‘This has gone completely out of control’?”

Tom: “I mean, he’s very happy that there are Lutheran regimes in princely states in Germany and in Scandinavia and in the Baltic. I think he’s more conflicted about the Protestantism of Switzerland, and definitely in England—I mean, he thinks Henry VIII is mad. But, I mean, whatever form that Protestantism takes, he’d rather that than what had existed before.”

Dom: “Really?”

Tom: “Yeah.”

Actually, Luther seems to have believed that traditional Roman Catholicism was better than the more radical elements of the Reformation, because at least there was some connection to the historic church. Those who denied the importance of the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper were, for Luther, of a different theological character than himself. Thus, after his meeting with Zwingli at the Marburg Colloquy of 1529, Luther concluded that his opponents had a different spirit than himself. At least those loyal to Rome believed that baptism and the Lord’s Supper delivered grace to the recipient. In this, Luther was different than most modern Lutherans, who see themselves more akin to other Protestants.

Thank you very much for taking the time to read and listen! If you enjoyed this consideration of Martin Luther’s life and teachings, you may enjoy my pair of novels set during the Reformation, which will be released in autumn 2024 and autumn 2025. Luther is a main character, along with Desiderius Erasmus and Philip Melanchthon. Stay tuned for updates!

Can’t get enough of me here? Why not follow me on Facebook, Twitter, Threads, or Instagram?

[1] Luther, Martin. Luther’s Works, Vol. 32 – Career of the Reformer II, ed. George W. Forell (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1958), 112-3.

[2] Luther, Martin. “Letter LXXVI – To the Elector Frederick of Saxony”, 5 March 1522, in The Letters of Martin Luther, trans. Margaret A. Currie (London: MacMillan and Company, 1908), 99.

I look forward to you books. A very interesting time in history and in the church.